Week 6: October 21, 2024

This blog is an ongoing project for Professor Ryan Enos' Election Analytics Course at Harvard College (GOV 1347, Fall 2024). It will be updated weekly with posts analyzing how different features impact the likelihood of Kamala Harris (D) or Donald Trump (R) winning the 2024 U.S. Presidential Election or winning specific states in the election. The blog will culminate in a final predictive model for the outcome of the general election.Context & Question

In this week's post, I focus on the application of Bayesian Models in election prediction. Bayesian statistics is based on the notion that the probability of an event occurring can be modeled as some function with some unknown parameter(s). When we first look at some event, our parameter value will be based on our *prior* beliefs regarding the process or event. But as we collect *data*, we update the parameter(s) to improve our predictions about whether the event will occur. Bayesian statistics stands in contrast to Frequentist statistics. Frequentists predict the probability of an event based on how many ties it's happened in the past (in a dataset, for example). They believe that a paramter has a fixed value and rather than updating it based on data, frequentists are prone to quantifying the *likelihood* that a parameter is equal to some given value, based on data. Bayesian models can be powerful in election analytics because datasets constantly change, and audiences/statisticians can update their understandings of probable outcomes based on them. Datasets can change as a result of updated polls, OR as election returns are collected during periods of Early/Mail-in Voting, which have grown in popularity over the past several years. In my model, I propose using both: I will ground my prior parameters in poll results (calling back to some elements of my post from September 21st) and update them conditional on early voting returns.The Data

The polling data in this week's post is broken down by state. Since I'm using the same data from my September 21st post, the latest polling average that I use for my prior probability is from September 16th, 2024. The early voting returns were obtained from the [Associated Press](https://apnews.com/hub/election-2024) and contain returns by party for all states that have started early voting. It's important to note that not all states have made early voting available yet, so only 40 states' returns are represented in this dataset.Building the Model

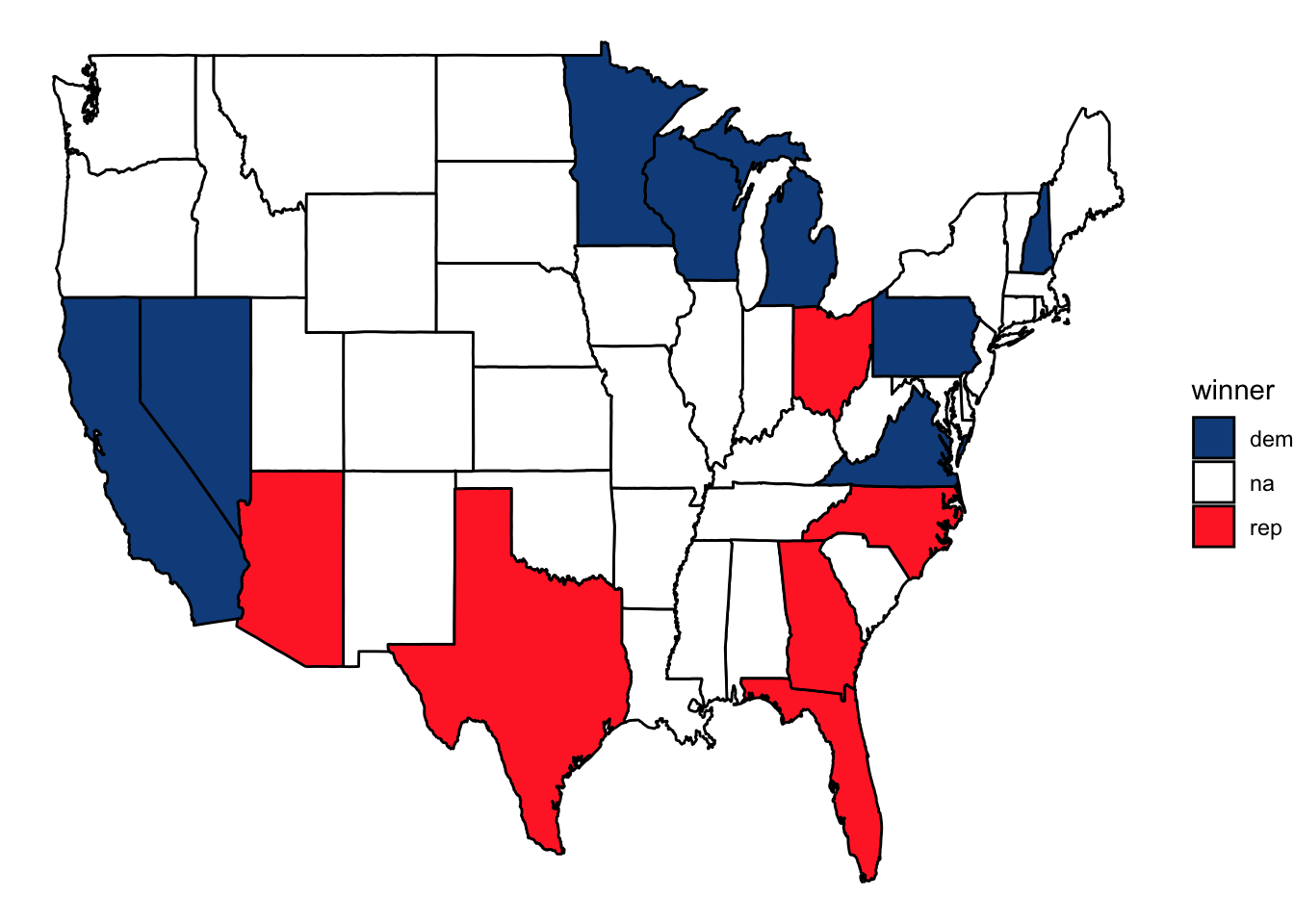

Let our prior belief about each candidate's performance in the election be represented by their last polling average. If we took polling averages from September 16th, 2024 to represent the election outcome, the electoral map would look like the following.

It’s worth noting that this dataset only contained polls for 15 states. Granted, many of them are swing states (i.e. Pennsylvania, Georgia, Michigan, and North Carolina), but our prediction and model would be more complete with access to data from all 50 states.

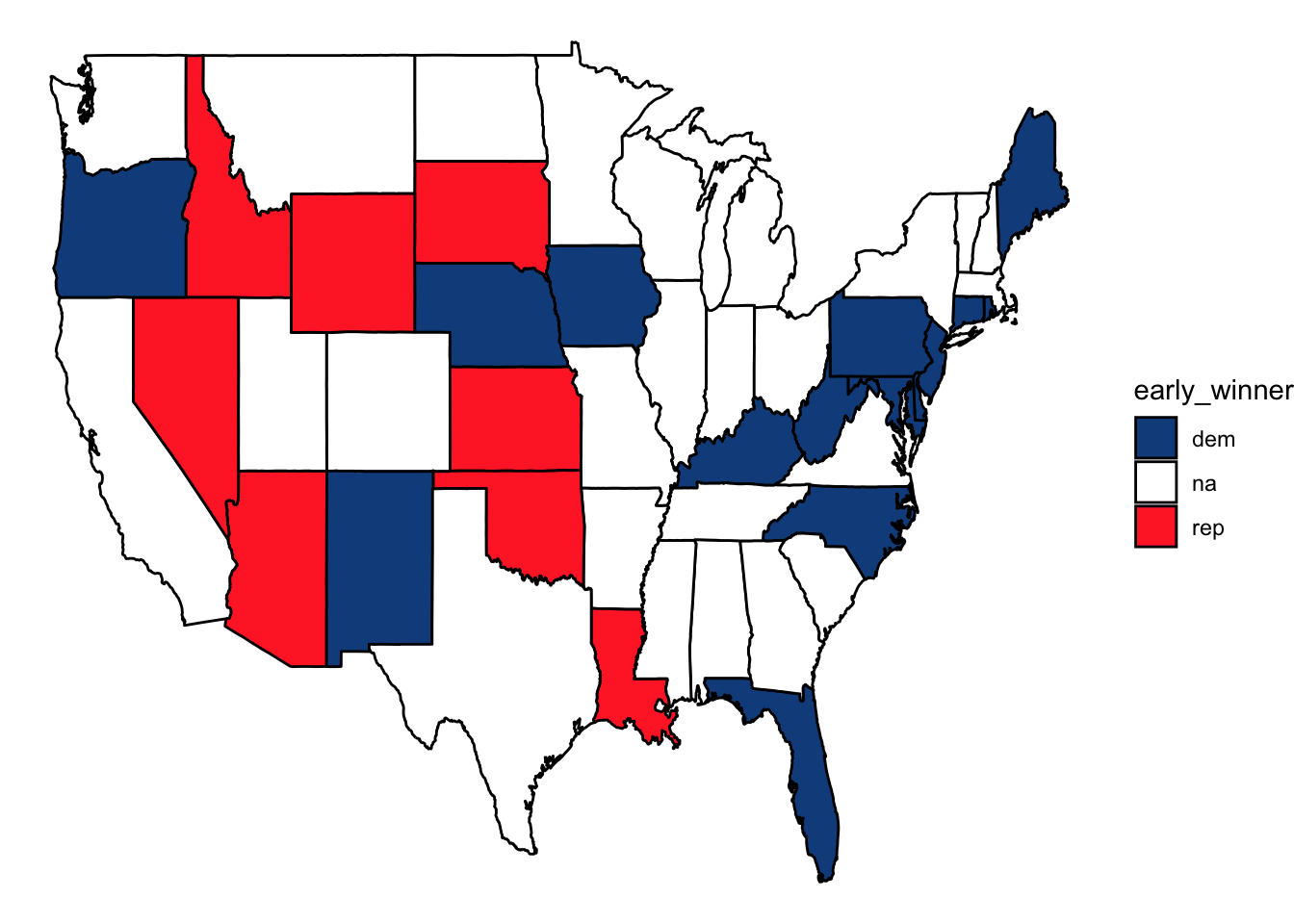

Next, I use visualize the election outcome based only on states for which early voting returns are available.

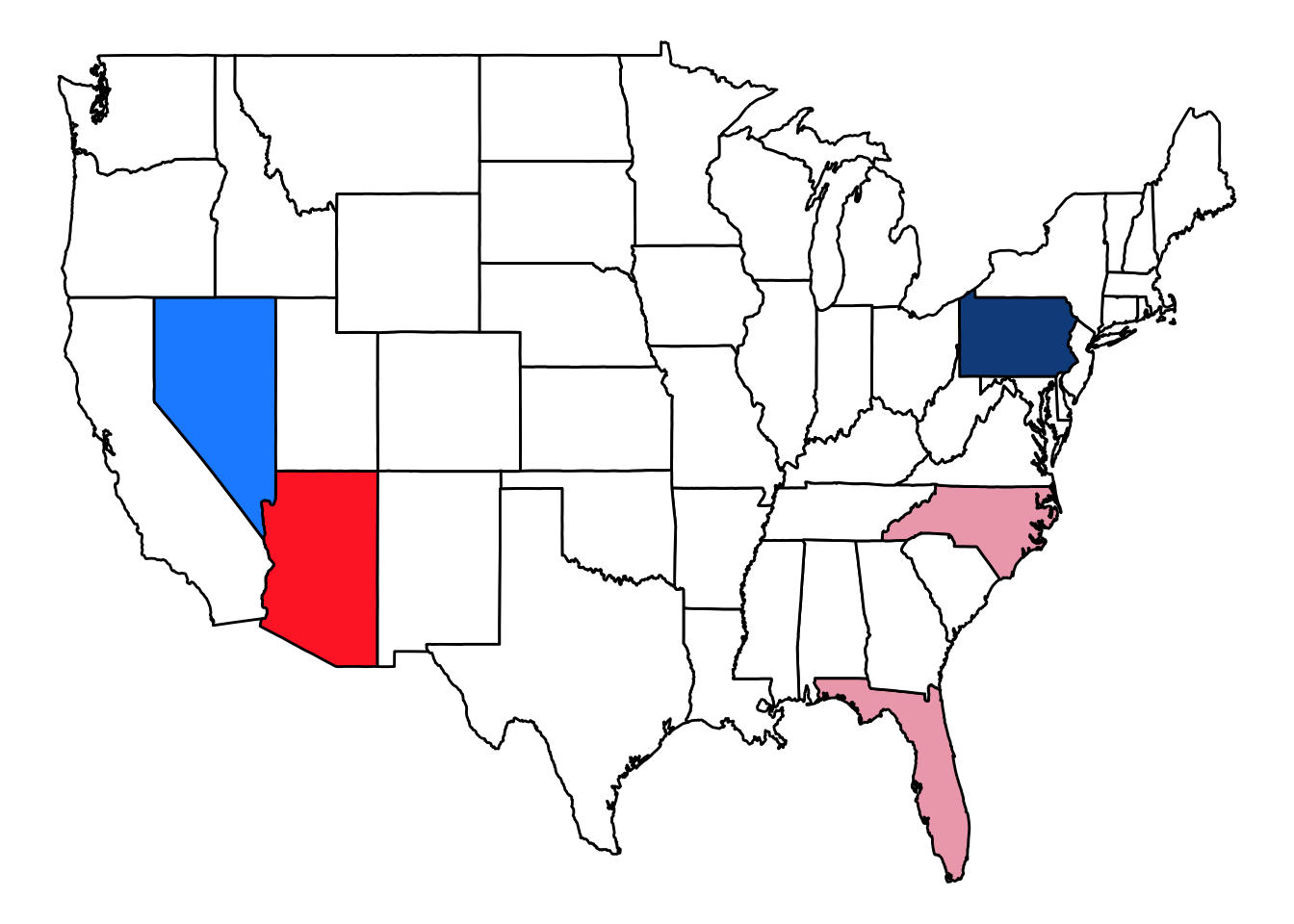

This final map shows which states’ outcomes are more certain versus less certain based on early voting returns. If a state that was shaded blue in the top map is now shaded a lighter shade of blue, it means that early returns make it seem less likely that the democratic candidate will win the state, and vice versa.

As we can see, early voting returns generally decreased the polls’ confidence in candidates, both Democratic and Republican. Only in Arizona and Pennsylvania did the early voting returns match up to the polling results. Otherwise, the opposite party than was leading the polls took the lead in early voting. There were only 5 states for which data about early voting returns and recent polling overlapped however.

Prediction for 2024

To update the probability that each candidate will win each state for which we have polling data from mid-September AND early voting returns, I will use the following form of Bayes' Rule. Let A be the event of a candidate winning the election based on polling data and let B be the event of that same candidate winning the election based on early voting returns. `$$P(A|B) = \frac{P(B|A)P(A)}{P(B)}$$` In this model, P(A) is the share of the polls that a candidate had and P(B) is the share of the early votes that the candidate has. P(B|A) is the probability that a candidate received their early voting share, given their latest polling average. This should be higher the closer together the polling average and early vote returns are, recognizing that, if polls are truly an accurate prediction of candidate vote share, the early voting returns should approach the polling average as more and more ballots are cast, by the Law of Large Numbers. That is, as of this week, polling averages may *not* be as closely linked to early voting returns as they will later in the election cycle and on election day. The table below shows updated predictions for the Democratic and Republican vote share, by state, based on early voting returns. This is done for each of the 5 states that we had *both* pollling data and early voting returns from.As we can see in the table above, this Bayesian model predicts that Kamala Harris will win in Arizona and Nevada, and that Donald Trump will win in North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Florida. I would like to repeat the analysis using more recent polling data, and early voting returns closer to election day in about 2 weeks.