Final Predictive Model for the 2024 Election

For my final election prediction, I performed OLS regressions for each state, based on the predictors that best explained each state's variance. I compiled a dataset with variables about candidate performance since 1972, as well as demographic data, economic data, historical turnout trends, ad spending, and polling, in each state. Then I fit an OLS model to each state, on all of the features, and chose the 5 with the highest `\(R^2\)` values. The `\(R^2\)` statistic measures how much variation in an outcome (like democratic vote share) can be explained by the given predictor. So by choosing to build a linear model based on predictors with high `\(R^2\)` values in each state, I hope to use the least possible predictors to capture the most possible nuance in each state. Then I fit another model on each state, using just the selected predictors based on `\(R^2\)`. To make the final predictons, I compiled a dataset of the same predictors, but from 2024, and predicted each state's 2-Party Democratic Vote Share from a multilinear regression for each state. It's important to note that, using this method, each state winds up having a different set of predictors used in its model. The reasons for using a state-by-state model and different predictors per state are both rooted in calcification. Calcification is the idea that, in the United States, the major political parties receive about equal public support, and winning an election is therefore about attaining a geographic spread of votes rather than the highest sum of votes.The Data

For this model, I made a dataset with over 50 predictors. It goes back to the election of 1972 and includes metrics about candidate polling averages; national CPI, GDP Growth, Unemployment Rate, and RDPI; education level, age distribution, and race by state; ads spending by state; previous turnout; and previous candidate performance. In cases where I had missing values, I decided to impute the column mean.Below is a table showing which predictors had the highest \(R^2\) values for each state. In this model, I chose to use the 5 highest \(R^2\) values, but there is room to fine-tune the model here. I could (1) vary the number of predictors used from each state, based on a threshold for the \(R^2\) value of the predictor, or based on a parameter (like the amount of variance explained before I stop incorporating new predictors). This might help make the features in each of my state-level models more uniform in terms of the variance they explain. Or I could (2) experiment changing the number of predictors used in all the states, but keep it the same between them and settle on a number of \(R^2\) predictors that provides predictions I’m happy with for most states.

Next, I gathered data about the 2024 Election Cycle, akin to what I had from previous cycles, and predicted the Democratic 2-Party Vote share. for the Voting Eligible Population and Number of Ballots cast, I used the forecasts by Michael McDonald since data about this doesn’t exist yet from 2024. I did however make my own forecast for voter turnout in each state based on early voting rates in 2024. I took early voting rates from November 2, 2020 and November 2, 2024 from the University of Florida’s Election Lab. Then I created a multiplier to project total votes from early votes, by dividing the total votes cast in each state in 2020 by the number of early votes cast in the state in 2020.

There is potential that the number of early ballots cast in 2020 may be higher OR lower than the number of early ballots cast in 2024. An argument for why they might be higher would be that the COVID crisis was at a peak in 2020, and any people used early/mail-in voting as an opportunity to avoid crowded polling places on election day, out fo public health concerns. A reason why the number of early ballots cast in 2020 would be lower than those in 2024 however is that, in 2024, people are more familiar with the early/mail-in voting process than they were in 2020, so they may be more inclined to use it. Similarly, on a state-by-state basis, if states changed their mail-in and early voting policies between 2020 and 2024, it may have been easier to vote early in one year than the other, leading to differing recorded numbers of people turning out early.

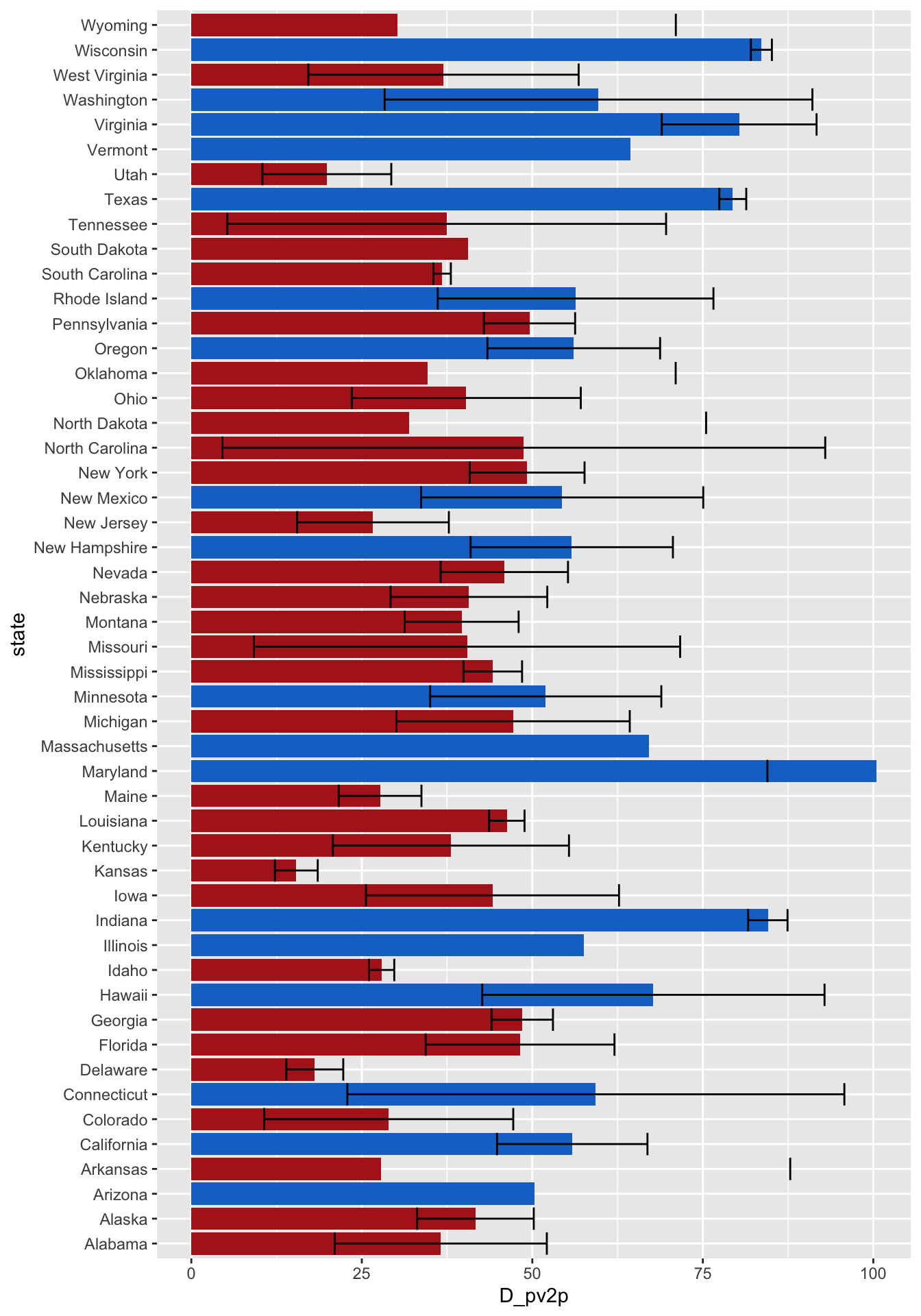

Below are my predictions for the two-party democratic vote share in each state in table format and then in a bar graph format. The error bars are based on calculation of the prediction from coefficients that were within a 95% Confidence Interval of the true coefficients.

As was the case with some of the predictions, some of the errors are particularly large, I’m looking at that of Arizona, Connecticut, and North Carolina in particular. Where there is only an upper cound for the error, it means that the lower bound suggested a negative vote share, which is uninterpretable in this context.

Model Reflections

There are a few odd-balls in the prediction set. For example, it suggests that Democrats could win 100% of the vote in Maryland (unrealistic), 83% of the vote in Wisconsin, 79% of the vote in Texas, 29% of the vote in Colorado, and 26% of the vote in New Jersey. This means that, for these states, this method of prediction or number of predictors is not the most well-suited. It is the price we pay for trying to fit one, standard model 50 diverse states with different populations, preferences, and trends. Another reason for the odd predictions could be that this model incorporates temporal data, going back to 1972. The political landscape in 1972 was vastly different than today's, so using a metric of candidate success in a state in 1972, may not correspond to their success in 2024. The same is true even for more recent elections: the features that may have correlated with success, or share of the vote in a state, in 200 or 2008 may not correlate with the share of the vote today. With extra time and ever-accessible data, I would look into building individualized models for the states that appear problematic in this forecast. However, this was an attempt at abstraction--defining one general model with a set of rules that could be applied to all states--while still accounting for some of the individual nuances between states. I'm interested to see how this model performs for the states that, at first glance, it seems to predict reasonably (i.e. Georgia, New Hampshire, Arizona, Florida).paged_table(as.data.frame(cbind(unique(big_data$state), as.vector(state_predictors))))